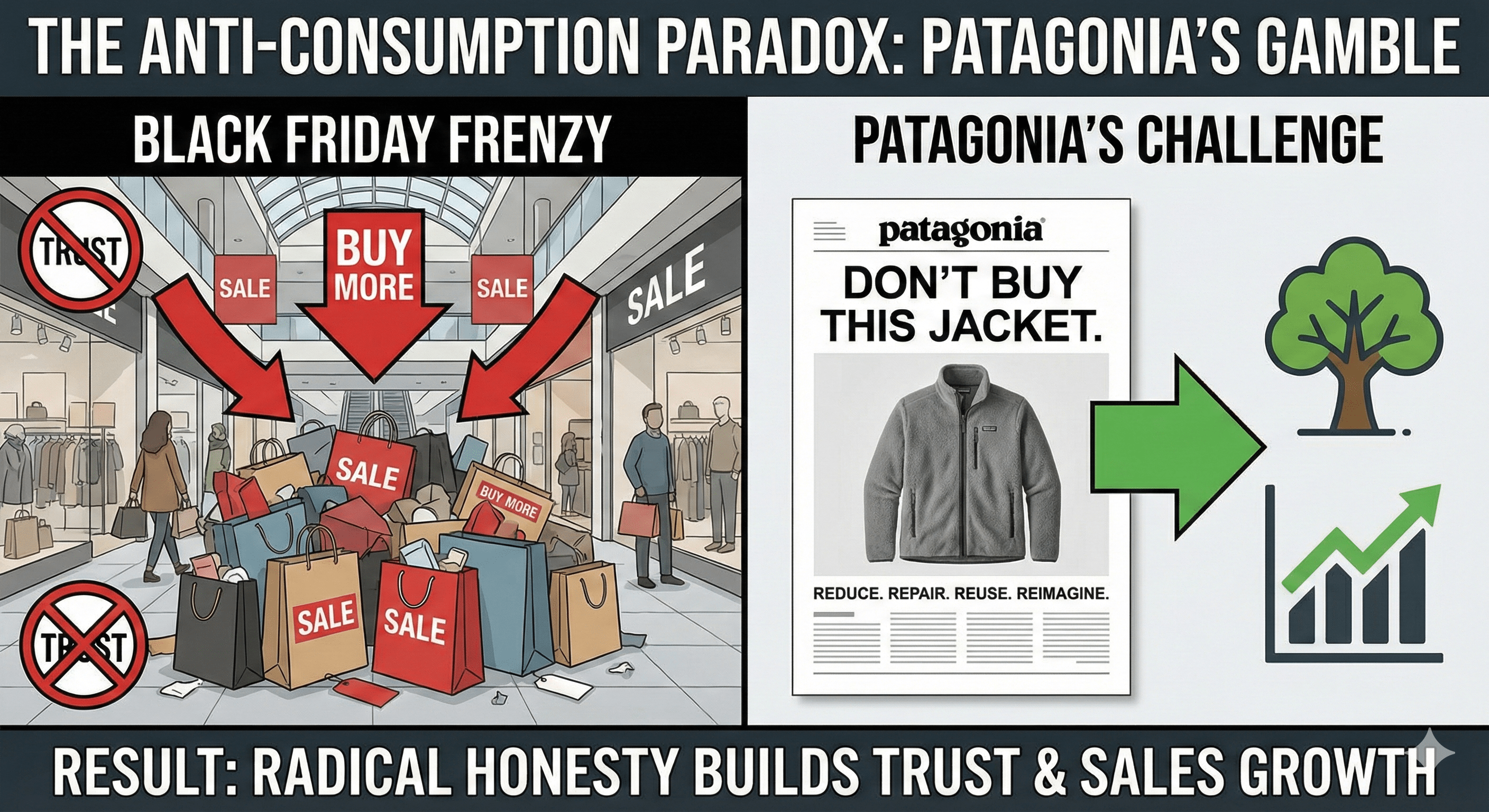

Patagonia’s “Don’t Buy This Jacket” campaign is one of the clearest examples of values-based marketing actually driving revenue instead of killing it. On Black Friday 2011—the biggest shopping day of the year—the outdoor apparel brand ran a full-page New York Times ad with a stark headline over an image of one of its best-selling fleece jackets: “DON’T BUY THIS JACKET.” The copy explained the environmental cost of making that product and urged people not to buy what they did not need. It was a direct challenge to consumerism from a company that made its money selling things, and it ended up strengthening loyalty and contributing to double-digit sales growth in the following year.

Market Context: Growth vs. Overconsumption

By 2011, Patagonia was already a respected outdoor brand known for technical quality and an environmental stance. But like every apparel company, it faced a structural contradiction: growth meant selling more units, while its mission emphasized reducing environmental harm from overconsumption, waste, and resource use. Black Friday and holiday shopping symbolized the exact behavior Patagonia publicly criticized—impulse buying and fast fashion.

At the same time, consumer attitudes were shifting. A growing segment—especially among outdoor enthusiasts and conscious consumers—was skeptical of traditional marketing and wary of “greenwashing.” These customers wanted proof that brands genuinely cared about the environment, not just slogans. Patagonia’s leadership, including founder Yvon Chouinard, believed that long-term brand trust and impact required radical honesty about the footprint of its products, even if it risked short-term sales.

The Specific Tactic: An Anti-Consumption Ad on the Biggest Shopping Day

The core tactic was to run a deliberately paradoxical, anti-consumption ad at the peak of consumer frenzy. The New York Times ad on Black Friday featured:

- A large product image of the R2 fleece jacket

- The headline “DON’T BUY THIS JACKET” in all caps

- Detailed copy breaking down the environmental cost of making that garment, including water usage, carbon emissions, and waste

- A call to action urging readers to “Don’t buy what you don’t need” and to think twice before purchasing anything

This was part of Patagonia’s broader Common Threads Initiative, which asked consumers to commit to five Rs: reduce, repair, reuse, recycle, and reimagine. The ad directed people not only to consider skipping purchases, but also to repair existing garments, buy used, and only buy new when truly necessary.

Instead of using Black Friday to push discounts and volume, Patagonia used it to question the entire premise of buying more.

The Insight: Radical Honesty Builds Trust and Differentiation

Patagonia’s leadership understood that authenticity and values can be a competitive advantage when consumers distrust marketing. Three intertwined insights underpinned the campaign:

- Purpose-Driven Consumers Were Growing

Research and internal observation showed a rising segment of purpose-driven consumers who made decisions based on alignment with their values, not just price and style. These customers were willing to pay a premium for brands that genuinely tried to reduce harm and were transparent about their impact. - Greenwashing Was Eroding Trust

Many apparel and lifestyle brands had started to use vague sustainability language—“eco-friendly,” “green,” “natural”—without meaningful action or disclosure. Patagonia believed that by being brutally specific about the environmental cost of its own products, it could stand apart. Numbers and concrete actions would be more credible than slogans. - Honesty About Tradeoffs Could Deepen Loyalty

By telling the uncomfortable truth—“even our better-made products still damage the planet”—Patagonia signaled that its mission constrained its business decisions. This could deepen emotional loyalty, making customers feel they were part of a cause, not just a transaction. The brand bet that, over time, this would outweigh any short-term loss of sales.

The campaign was designed not just to spark buzz, but to align marketing with the company’s core mission: “We’re in business to save our home planet.”

The Execution: From One Ad to a System of Actions

“Don’t Buy This Jacket” was not a one-off provocation; it sat on top of a broader operational and communications system.

The New York Times Ad Itself

The Black Friday 2011 ad grabbed attention with its contradiction. The copy went beyond a slogan, describing how the featured jacket:

- Required large quantities of water to produce

- Generated significant carbon emissions

- Created waste and environmental impact even though it used recycled materials

The ad concluded with a call to consumers to reconsider their buying habits and to join Patagonia in reducing unnecessary consumption. It was simultaneously a confession, a challenge, and an invitation.

The Common Threads Initiative

Patagonia linked the ad to its Common Threads Initiative, which asked customers to sign a formal pledge:

- Reduce: Buy only what you need

- Repair: Fix what breaks

- Reuse: Sell or pass along what you no longer use

- Recycle: Return worn-out items so materials can be reused

- Reimagine: Support a new way of doing business that does not depend on endless growth

This initiative created a framework that made the ad more than a stunt. It gave consumers concrete actions and turned anti-consumption into a shared project between brand and customer.

Worn Wear and Repair Programs

To make “Don’t buy this jacket” credible, Patagonia backed it up with services and programs:

- The Worn Wear program encouraged people to trade in used Patagonia gear, buy second-hand products, and repair items to extend their life.

- Patagonia invested in mobile repair trucks, in-store repair stations, and published DIY repair guides.

- The company committed to a lifetime repair policy for many items, emphasizing durability over disposability.

These actions showed that Patagonia was willing to sacrifice some new product sales in order to keep existing products in use longer.

Radical Supply Chain Transparency

Patagonia also worked to make its supply chain unusually transparent:

- The Footprint Chronicles and Our Footprint tools on its website allowed customers to see information about the environmental and social impact of specific products and factories.

- The company published detailed information about its use of organic cotton, recycled polyester, fair-trade factories, and ongoing efforts to reduce impact and improve labor practices.

- It openly discussed areas needing improvement, acknowledging that it was not perfectly sustainable but continuously working toward better practices.

This level of transparency, rare in apparel, reinforced the credibility of a campaign that asked people to consume less.

The Result: Sales Growth and Stronger Brand Equity

The paradoxical outcome of “Don’t Buy This Jacket” is central to its value as a case study.

In the year following the campaign and the broader “buy less” push:

- Patagonia’s sales increased by roughly one-third, reaching around $543 million, compared to about $400 million before the initiative.

- The next year, sales reportedly rose again to approximately $575 million, adding tens of millions in incremental revenue.

- Case writers and analysts often cite a roughly 30% sales boost in the nine months following the ad, despite the brand explicitly telling people to buy less.

Beyond numbers, the campaign generated:

- Extensive media coverage, with articles, blogs, and business school case studies dissecting the “Don’t Buy This Jacket” ad as a landmark in cause marketing and authenticity.

- Increased brand differentiation in a crowded outdoor apparel market, positioning Patagonia not just as “high-quality gear” but as a leader in responsible business.

- A stronger emotional bond with customers who saw their purchases as supporting a company that aligned with their environmental values.

Patagonia showed that values-based marketing, if backed by real operations, can drive both impact and profit.

Why It Worked: The Transferable Principles

For students and marketers, Patagonia’s success here is not a fluke. It rests on several principles that can be applied in other categories.

Align Marketing With Real Operations

The ad would have rung hollow if Patagonia did not have:

- Durable, repairable products

- Repair and resale programs (Worn Wear)

- Transparent supply chain reporting

- A history of environmental activism and philanthropy

Because these systems were in place, the campaign was credible. The marketing did not create the values; it amplified them.

Transferable principle: Values-based messaging must reflect genuine operational commitments. Before telling a bold story, ensure you have real policies, programs, and metrics to back it up.

Embrace the Tension Instead of Hiding It

Patagonia did not pretend that buying its products had no environmental cost. It highlighted the tension between selling gear and protecting the planet, then invited customers into that complexity. This honesty built trust.

Transferable principle: When there is an inherent contradiction in your business model (e.g., growth vs. sustainability, convenience vs. privacy), acknowledging and working through it openly can strengthen your brand more than ignoring it.

Use Contrarian Messaging to Stand Out

On a day when virtually every other brand shouted “Buy more, save more,” Patagonia said “Don’t buy this.” The contrast alone earned attention and coverage. The contrarian stance was not empty provocation; it was rooted in a coherent mission.

Transferable principle: Look for moments when your category all moves in one direction (Black Friday, product launches, industry trends). A principled, contrarian message can cut through the noise if it is aligned with your brand’s core values.

Build a Community Around Shared Values

The Common Threads pledge and Worn Wear programs turned Patagonia’s customers into participants in a shared project: reducing overconsumption and waste. This created community and made each customer feel part of something bigger than a purchase.

Transferable principle: Values-based marketing works best when you give people a way to act on those values. Think in terms of programs and behaviors, not just messages.

Think Long-Term Brand Equity Over Short-Term Volume

Patagonia was willing to risk short-term sales to deepen long-term loyalty and alignment with its mission. The bet was that purpose-driven consumers would remember, respect, and reward that stance over time. The subsequent growth validated this.

Transferable principle: Some of the most powerful campaigns may look “irrational” on a quarterly P&L but build enduring brand equity that compounds over years.

How Students Can Apply This

To turn Patagonia’s “Don’t Buy This Jacket” into practical learning:

- Exercise 1 – Values Audit:

Choose a brand you know. Identify its stated values. Then ask: What would be the “Patagonia move” in this category—a campaign that highlights a tension between short-term sales and long-term values? - Exercise 2 – Anti-Message Concept:

Write a mock ad where your brand tells consumers not to do something that would normally drive sales (e.g., “Don’t upgrade yet,” “Don’t order delivery tonight”). Explain what operational commitments would be needed to make this credible. - Exercise 3 – Program Design:

Design a simple “Common Threads”-style program for another industry (tech, finance, beauty) that turns values into behaviors: pledges, repair/repairability, reuse, or transparency initiatives.

The core marketing principle: When values are real and operationalized, telling the uncomfortable truth—even if it appears to undermine sales—can create trust, loyalty, and ultimately stronger business results than conventional hard-sell tactics.

Sources (APA Format)

- Bazaarvoice. (2022, October 26). How Patagonia is using cause marketing to define their brand and drive sales. Bazaarvoice. https://www.bazaarvoice.com/blog/how-patagonia-is-using-cause-marketing-to-define-their-brand-and-drive-sales/

- Gelles, D. (2025, November 27). The secret history of “Don’t Buy This Jacket.” The Moral Leader (Substack). https://davidgelles.substack.com/p/the-secret-history-of-dont-buy-this

- Great Ideas for Teaching Marketing. (2023). Patagonia case study: Marketing to anti-consumers [PDF]. Great Ideas for Teaching Marketing. https://www.greatideasforteachingmarketing.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Patagonia-Case-Study-Marketing-to-Anti-Consumers.pdf

- Harvard Business Review. (2012, November 22). Patagonia’s provocative Black Friday campaign. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2012/11/patagonias-provocative-black-f

- IMD. (2015, November 30). Patagonia’s sustainability strategy: Don’t buy our products. IMD. https://www.imd.org/research-knowledge/sustainability/case-studies/patagonia-s-sustainability-strategy-don-t-buy-our-products/

- Marketing Week. (2014, October 16). Case study: Patagonia’s ‘Don’t buy this jacket’ campaign. Marketing Week. https://www.marketingweek.com/case-study-patagonias-dont-buy-this-jacket-campaign/

- Patagonia. (2011, November 24). Don’t buy this jacket, Black Friday and the New York Times. Patagonia. https://www.patagonia.com/stories/planet/activism/dont-buy-this-jacket-black-friday-and-the-new-york-times/story-18615.html

- Patagonia. (n.d.). Responsible purchasing practices. Patagonia. https://www.patagonia.com/our-footprint/responsible-purchasing-practices.html

- The Case Centre. (2019, June 4). Patagonia’s sustainability strategy: Don’t buy our products. The Case Centre. https://www.thecasecentre.org/products/view?id=137097

- Zuno Carbon. (2024, April 17). Lessons from Patagonia’s sustainable supply chain. Zuno Carbon. https://www.zunocarbon.com/blog/patagonia-supply-chain

- Causeartist. (2025, November 26). Business case study: Patagonia. Causeartist. https://www.causeartist.com/case-study-patagonia/